Decentralized Solar

A few years ago, solar seemed like a small slice of future electricity generation: it was expensive, took up a lot of space, and was intermittent. Recently, the plummeting cost and increasing efficiency of solar panels has combined with a similar revolution in lithium-ion batteries has transformed solar into a huge part of the future mix. What's particularly wild about it is the potential for decentralization where individuals and isolated areas can push the changes forward themselves.

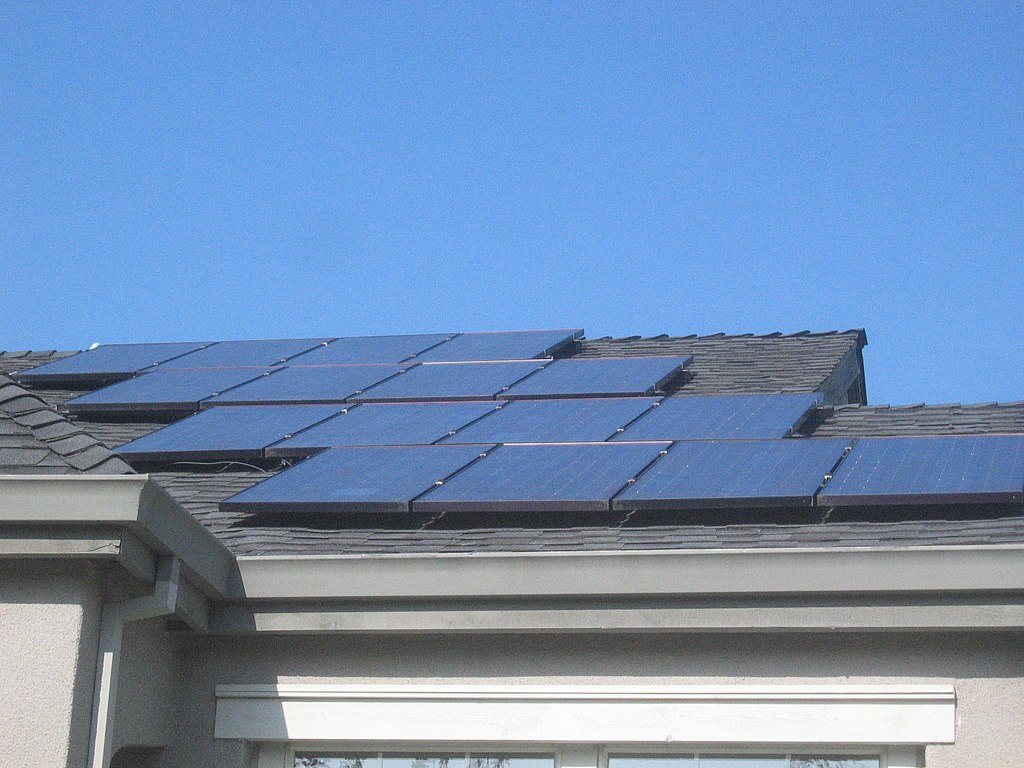

|

| Credit: Roland Tanglao from Vancouver, Canada. 2004. |

Decentralization

Solar power uniquely requires no external inputs other than the original generation capacity (i.e. fuel). Even other renewable systems like geothermal or wind have much larger footprints in that they must be professionally installed, while solar panels can be purchased and hung by a homeowner or renter with tools no more sophisticated than a screwdriver.

In Europe, regulations have created a space for "balcony solar" (article in Wired, thank you Cory Doctorow for linking this), where even apartment-renters can install small solar panels and plug them directly into their houses and appliances to defray electricity costs. The panels are small - less than 800 watts / 0.8 KW), but assuming average power = 25% of peak capacity, that's still 4.8 KWh / day, which is roughly a quarter of e.g. my household electricity use. US building codes are behind Europe in this way, and so unfortunately those commercially-available panels aren't available here.

But the plunging costs of battery technology (thanks again Mr. Doctorow) have opened the market for a ~$3000 solar system that consists of a battery and a few panels with minimal permanent installation. Per an example in The American Prospect "A Far Cheaper Way to Do Rooftop Solar," a standalone battery and set of 5x 460-watt panels (2.3 KW or 13.8 KWh/day) could run your refrigerator or air conditioner directly (i.e. plug that appliance into the battery) where you wouldn't need to wire anything into your home's power wires. This would require more manual work (manually plugging in the power-hungry appliance(s) and ensuring the battery doesn't get over-discharged), but at an extremely low cost it defrays power bills and provides a blackout-resistant backup system without the noise and air-poisoning aspects of a generator. In addition, it works independent of the age of the house's roof or how many open breakers are available in the house's wiring panel.

Resiliency

Hurricane Maria in 2017 took down the entirety of Puerto Rico's power grid. Casa Pueblo, a local community center, had a solar array which allowed it to maintain power for the building, phone charging for the community, a local radio station, and other services. This made it a case study in solar improving resiliency in disasters.

As with the battery + panel option above, solar greatly improves our ability to survive the minor disasters of life unscathed. The ability to stay in one's own house during a blackout is primarily enabled by a) food staying cold, and b) heat/cooling being available. A fridge might use 800 watts, and an air conditioner can pull up to 5,000 watts. A gas furnace blower motor shouldn't draw much, but an electric heat pump keeping the house warm might draw roughly that amount.

So a small-ish battery (3-5 KWh) could easily keep the fridge going for a full day (and many models can be recharged at an electric car recharging station), but if the outside temperatures are very hot or very cold then people might need to evacuate to somewhere with power.

- Related: "EV Charging Tribulations"

When coupled with electric vehicles and other electrification (e.g. heat pumps), community resilience is greatly improved. In a major disaster or power outage, gas-powered cars and generators may seem more resilient, but gasoline and diesel rely on transportation networks to reach your local pump. Gas stations rely on electricity to pump gas from their tanks into cars and trucks. Very quickly all of the machinery of society can halt. In contrast, a solar community maintains some level of mobility for much longer, with the limiting factors being food and spare parts (which are also concerns for a gas-powered community).

Personal Impact

As much as I'd like to invest in more solar right now, now is not my time to spend extra money. Instead, I am focusing on ensuring that future-me has options as solar marches on. This includes looking for opportunities to upgrade our electrical panel to accept electric hot-water heaters, heat pumps, electric-vehicle charging, and a "generator" panel (that disconnects the house from the grid and/or provides power to only certain outlets for essential devices.

House batteries are enough to keep the fridge cold and run the furnace motor, but electric car batteries are huge: my Hyundai Ioniq5 stores up to 72 KWh, or enough for 2.5 days of normal house power consumption - even longer when we're only running the essentials. Most cars don't provide "vehicle to load" in any substantial way, but some do (e.g. the Ford F150 Lightning) and there's no mechanical / electrical reason why more couldn't. I imagine that "vehicle to vehicle" will also become commonly available to enable "buddy refueling" when people run out of charge on the road.

Using the car to power the house has the tradeoff that it reduces the ability to evacuate if needed, but having the option to make that trade would be extremely helpful. Especially if a blackout is local, imagine a world where you power your house with your car, let your car battery run down to 50%, then drive 15-20 minutes to a high-speed charger, top off, and then bring the car home to provide power again. Not the same as "not in a blackout," but comfortable enough that the food stays cold, the microwave can work, and the house stays at a livable temperature.

Comments

Post a Comment