Supply Chain Resilience and Deterrence

I’m back from my vacation and so it’s time to get back on schedule. Today we’re talking about supply chain resiliency and industrialized warfare. I’ll address the “why industry matters” first and then talk about resiliency.

Full Mobilization

Since February 2022 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, industrialized warfare has become relevant again in a way not since the end of the Second World War. Around 2010 I remember reading through a book of military aircraft through history which noted total production numbers for each type. Just one aircraft, the P-51 Mustang, totaled over 15,000 aircraft produced over only four years. I compared that to the F-35, which was noted for being a gigantic modern program, had a total planned production of 5,000 aircraft over decades. Even accounting for additional complexity on the F-35, clearly the US is not engaged in wartime production.

More recently (2021) I had another reminder of the power of industry in warfare. Shattered Sword by Johnathan Parshall and Anthony Tully is a recent re-examination of the Battle of Midway in the Pacific theater in World War II: commonly referred to as a turning point in the war, the book’s authors argue that even if Japan had won the battle, the US would have won the war eventually. Page 122 says why:

The Japanese believed they currently outnumbered the U.S. Navy eleven carriers (six heavy and five light) to six (five heavy and one light). If the Imperial Navy was to preserve for itself the freedom of action that had thus far characterized its operations, it was essential to also conserve its numerical superiority, particularly in heavy carriers. Every senior Japanese officer knew that this current numerical ascendancy was bound to be transient The Americans were known to have more than a dozen Essex-class fleet [heavy] carriers building, in addition to several light fleet units comparable to Shoho and Zhiho [Japanese light carriers]. Japan could not hope to match this output.

In my e-reader I highlighted this section and noted it “Oh snap!”. To emphasize: the to-this-point dominant Japanese fleet had a small edge of one heavy carrier (six versus five). Under construction the US had twice the entire pre-Midway Japanese carrier fleet. By contrast, Japan had maybe one or two carriers expected to complete in the same period.

Deterrence

When a potentially-hostile power decides whether to attack, one of the key questions they must answer is “would we win?” If the answer is “yes”, they might still not attack, but if the answer is “no”, they are almost guaranteed not to. Why would someone start a fight they know they’ll lose? Now, the people making the decision might be mistaken about their own strength or that of their opponents (see Napoleon in Russia, Germany in World War II, Russia in Ukraine starting in February 2022), but they will try to assess relative strength. Further, the strengths that must be assessed are not only the forces currently deployed, but what might become available. So anyone considering attacking an industrialized country must assess each side’s ability to replace the people, systems, and ammunition that get used up during the conflict. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a current example of this: after Russia’s initial attempt to take Kiev failed, the war has swayed based on who is able to put more people, tanks, artillery shells, and various missiles and drones on the battlefield. Lack of artillery ammunition hamstrung Ukraine in 2024 until new supplies became available, and Russia will soon run out of Soviet-era armored vehicles to restore and deploy.

What’s dangerous about this to U.S. deterrence is that ammunition consumption for a localized war in Europe has exceeded the production capacity of the U.S. and its allies. This is NOT an argument to stop supplying Ukraine; it’s an argument to USE our supplying of Ukraine to ramp up our (U.S. and allies) production lines. If an adversary believes that we cannot replace ammunition at the rate that we use it, they only need to survive until our stocks are depleted and then they win by default. On the other hand, if our adversaries see that we can supply Ukraine, recharge our own drawn-down inventories, and then grow them further (because all of the conflicts of the past few years have emphasized that fighting takes a lot of materiel: not just ammunition but also anti-missile interceptors!), then they may decide that they can’t win a drawn-out conflict and choose not to start one.

Supply Chain Resilience

When Russia invaded Ukraine, I was the Senior Manager for Work Transfer at my company: that meant that I owned every part that was made at supplier “A” today and needed to be made at supplier “B” tomorrow. And it turns out that getting supplier “B” into production is really hard! Supplier “B” might have made very similar parts for the same customer for years; they might have access to identical blueprints; they might even have nearly-identical metal-cutting machines on their production floor! But differences in skill, programming, and drawing interpretation (to name a few) will still lead to snags in getting the parts running at the new supplier.

I started thinking about what I’d have to do if my management came and told me to get serious about military production. In World War II, military units might lose ~1% of their force even when not in pitched battle: repairs, maintenance, small actions. That means that just to hold our own, we’d need to replace nearly a third of the force every month! An aircraft carrier air wing includes 40+ strike fighters alone (and the Cold War wing was more like 60). So that means that for ONE carrier involved in sustained combat with a peacetime air wing, we need ~12 F/A-18s repaired or new-build per month, triple our production rate. Yikes!

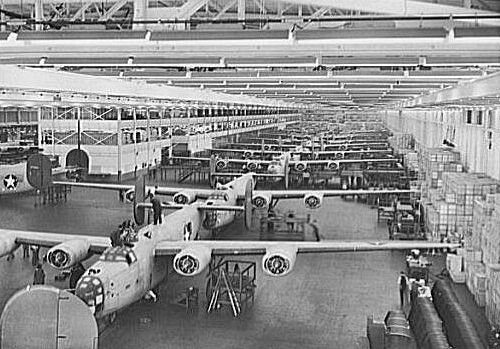

|

| Willow Run peaked at nearly one bomber per hour! |

Where would the capacity to increase production come from? In the past, a vast and diverse set of “Mom and Pop” machine shops were scattered across the U.S. Although they tried to keep their production lines full, they often had some spare capacity (in the form of only running one or two shifts, a balky machine that they never bothered to use but could in an emergency, slack in case of needing to make up for a quality issue, etc.). As the industry consolidated, a lot of that excess was removed in the name of efficiency: keep all the machines working 24 hours and sell the balky machine for scrap so we can save on leased space! Larger prime and tier-1 companies are also harder to work with (longer and more onerous contract terms, bespoke supplier portals, multitudes of people to talk to depending on the topic), so why shouldn’t Mom and Pop sell their shop and let the industry consolidate? I’ve seen incredibly capable and agile small shops get transformed into mediocre medium or large shops by the demands of their new owners, by their customers, or both. In one case we had a “job shop” that our test lab loved because they could turn out custom equipment for qualification quickly; now we have them doing serial production and they struggle with small custom orders.

Conclusion

Industrial capacity still matters because it keeps the peace. And treasure your small eccentric suppliers because they’re the ones who can help you out when you need something quick. And as someone who has done a lot of risk management in their career, please keep a capacity reserve at your suppliers and in your own in-house production for inevitable quality issues!

If you have any comments, please reach out to me at blog@saprobst.com or this page is cross-posted at LinkedIn and you can leave a comment there

Comments

Post a Comment